Hi-Stat Vox No. 25 (January 17, 2013)

The Reduction of School Days in Japan Increased Educational Inequality

Daiji Kawaguchi

Associate Professor, Faculty of Economics, Hitotsubashi University

One of the major objectives of compulsory education is to assure uniform educational opportunities for all children regardless of their socioeconomic background. For that reason, most advanced countries provide compulsory education as well as text books free of charge. At the same time, it has been widely observed in countries around the world that children's educational attainment is closely linked to the educational attainment of their parents, giving rise to intergenerational persistence in educational attainment. As a result, one would expect that an increase in the number of years of compulsory education will raise the years of schooling mainly of children born to parents with low educational attainment and hence weaken the link between parents' and children's educational attainment. Empirical studies using data for Sweden and Norway suggest that this indeed appears to be the case.

However, the total amount of compulsory education children receive depends not only on the number of years of compulsory education, but also on the amount of lessons within a year, which in turn depends on the number of school days and the number of school hours in a day. This means that intergenerational persistence in educational attainment may also be influenced by the number of school days a year that a country adopts. Of relevance in this context are studies that suggest that the socioeconomic gap in students' achievement tends to widen after summer breaks, which is thought to reflect heterogeneity in the home environment, in that some students continue to study during the summer break, while others do not. These findings provide indirect evidence regarding the interplay among schooling time, socioeconomic background, and academic achievement. However, it appears that to date no studies have directly examined this issue. Against this background, Kawaguchi (2013), a Hitotsubashi University Global COE Discussion Paper, seeks to examine how the decrease in school days in Japan through the introduction of the five-day school week in public primary and junior high schools affected the intergenerational persistence in educational attainment. This column provides an outline of the study.

Compulsory education in Japan consists of primary and junior high school. Until summer 1992, lessons were held every Saturday morning, which more or less corresponds to the fact that until the early 1990s, many employees also worked until noon on Saturdays. However, the 1988 revision of the Labor Standards Act reduced the legal work hours from 48 to 40 hours a week, and by the mid-1990s, most employees had two days off a week. Against this background, there were increasing demands for schools to follow suit in order to give teaching staff two days off in line with other employees and to allow children to spend Saturdays with their parents, and the five-day school week was gradually introduced. To start with, the second Saturday of each month became a holiday at public primary and junior high schools from September 1992. From April 1995, the second and the fourth Saturday then also became holidays, and finally, from April 2002, all Saturdays became holidays.

Kawaguchi (2013) examines how the fact that in 2002 the first and the third (and then the fifth) Saturday became additional school holidays affected children's study time and academic performance, and how changes therein differed according to children's socioeconomic background measured in terms of parents' educational attainment. To examine changes in children's study time, the study focuses on the time use of ninth graders (third-year junior high school students) using microdata of the “Survey on Time Use and Leisure Activities,” a large-scale survey on time use conducted by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. The survey, which is conducted once every five years and surveys approximately 200,000 persons over the age of nine, asks respondents about their time use on two designated consecutive days among nine days from the second Saturday to the third Saturday of October. Respondents are asked to report what they did on those two days in 15 minute intervals by choosing among 20 different options such as “school work,” “sleeping,” etc. Among these, “school work,” “commuting to/from school,” and “studying and researching” were treated as the total time spent on studying.

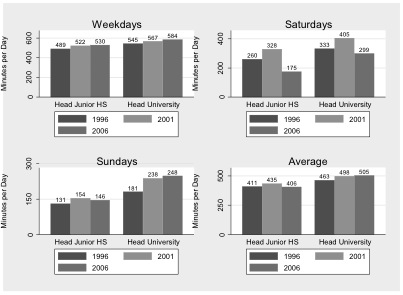

Figure 1 shows ninth graders' average study time by day of the week and the household head's educational attainment.

Figure 1. Ninth graders' average study time (in minutes)

Let us begin by comparing the results for 2001 and 2006, which lie on either side of 2002, when, in addition to the second Saturday, which had been a holiday since 1995, the third Saturday became a holiday. The figure shows that ninth graders' Saturday study time decreased irrespective of the household head's educational attainment. However, whereas the decrease in the case of junior high school-educated household heads was 153 minutes, that in the case of university-educated household heads was only 106 minutes. Moreover, although the weekday study time increased between 2001 and 2006 for all households, the increase for ninth graders in junior high school-educated households was only 8 minutes, while it was 17 minutes in university-educated households. In addition, whereas the study time on Sundays decreased by 8 minutes for ninth graders in junior high school-educated households, it increased by 10 minutes university-educated households.

Thus, looking at the changes in study time by day of the week, the results suggest that in the case of households headed by university graduates, the decrease in ninth graders' Saturday study time was compensated for by an increase in study time on weekdays and Sundays; on the other hand, in the case of ninth graders in households headed by junior high school graduates, almost no such compensatory behavior can be observed. More concretely, it seems that in the case of a home environment in which parents are university-educated, the decrease in Saturday lessons was compensated for by sending the child to cram school on weekday evenings and on weekends. Therefore, calculating the average daily study time (by using the sampling weights in the data, which are roughly 5 times larger for weekdays than for weekend days, to calculate the daily average of time use over 7 days), that of ninth graders in households headed by a junior high school graduate decreased by 29 minutes, while that of ninth graders in university graduate-headed households increased by 7 minutes.

Of course, a possible reason for this divergence could be an underlying long-term trend in growing inequality in study time. That this is not the case, however, is illustrated by the fact that between 1996 and 2001, the average study time of ninth graders increased in both junior high school-educated and university-educated households, and the increase was very similar - 24 minutes in the former case versus 35 minutes in the latter.

Moreover, investigating to what extent the change in ninth graders' study time depends on parents' educational attainment using regression analysis, it is found that parents' educational attainment is a statistically significant determinant of the change in study time between 2001 and 2006, while this is not the case between 1996 and 2001. The results remain qualitatively unchanged when including prefecture and year fixed effects in the estimation. Furthermore, examining the change in time use on the second and third Saturdays in 2001 and 2006 shows that the dependence of children's study time on parents' educational attainment changed only for the third Saturday, which became an additional holiday. Overall, the various results show that the introduction of the five-day school week increased the dependence of children's study time on parents' educational attainment.

Looking at the regression results in more detail, the value of the coefficient showing the dependence of average daily study time on parents' educational attainment for 2001 was 6.67. This implies that an additional year of household head education is associated with an increase in children's daily study time by 6.67 minutes. Put differently, children of university-educated household heads studied 27 minutes more per day than children of high school-educated household heads. For 2006, this coefficient increases to 12.34, implying that children of university-educated household heads studied 49 minutes more per day than children of high school-educated household heads. Thus, in the 5-year period from 2001 to 2006 the coefficient increased by 85%.

How does this increase in inequality in study time among ninth graders with different socioeconomic backgrounds affect their academic performance? In order to examine this question, Kawaguchi (2013) analyzed microdata of the 1999 and 2003 waves of the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS), which assesses the mathematics and science competencies of eighth graders in several dozen countries around the world, and the 2000 and 2003 waves of the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), which assesses the competencies in reading, mathematics, and science of 15-year-olds in OECD countries. Unfortunately, the 1999 TIMSS and the 2000 PISA study do not contain information on parents' educational attainment; however, they do contain information on the number of books in the home, which tends to be strongly correlated with parents' educational attainment and can therefore be used to predict parents' educational attainment. Using this information, Kawaguchi (2013) examines the relationship between children's test scores and parents' educational attainment.

The results for eight graders show that, in 1999, an additional year of predicted parental education increased the test score by about 0.1 standard deviations. This implies that the average test score between children with high school-educated parents and with university-educated parents differed by about 4.0 standard deviations. This result in itself is not particularly remarkable, since it is well-known that children's academic achievement is closely correlated to parent's educational attainment. What is noteworthy, however, is that for 2003, i.e., after the full implementation of the five-day school week, the coefficient for an additional year of predicted parental education rises to approximately 0.12 standard deviations, which is about 20% higher than the value for 1999. In other words, the gap between children with high school-educated parents and with university-educated parents rose to about 0.48 standard deviations. While on their own these results for test scores do not necessarily provide conclusive evidence that the full implementation of the five-day school week resulted in an increase in educational inequality across socioeconomic groups, taken together with the above-mentioned increase in inequality in study time, it seems natural to assume that the two are causally related. Furthermore, because children's academic results in eighth grade are likely to directly affect the quality of the high school to which they will be able to progress and, by extension, the probability that they will attend university, the growing inequality in academic achievement is likely to contribute to an increase socioeconomic disparities in lifetime earnings, thus presenting a major social problem.

In sum, the empirical analysis in Kawaguchi (2013) shows that the full implementation of the five-day school week has led to an increase in socioeconomic disparities in both study time and test scores. Using the relationship between the two, it is possible to indirectly estimate the effect of study time on academic results. Doing so suggests that an additional minute of daily study time increases test scores by about 0.15 standard deviations. In other words, an additional hour of study a day raises the test score by 9 standard deviations, indicating that study time is a major determinant of academic achievement. This suggests that providing an environment that increases the study time of children whose parents have only completed junior high school themselves and whose study time has actually decreased as a result of the full implementation of the five-day school week would help to reduce socioeconomic inequality in academic achievement.

In fact, against the background of concerns that the decline in the demands of compulsory education in Japan due to the full implementation of the five-day school week and the “thinning out” of the curriculum have led to a decline in average academic achievement, an increasing number of schools have started to offer supplementary classes on Saturdays. Attempts such as these not only can help to raise average academic achievement, but also are likely to raise the achievement of students from a low socioeconomic background and thus potentially help to decrease inequality between students from different socioeconomic groups.

References

Kawaguchi, Daiji. 2013. “Fewer School Days, More Inequality,” Hitotsubashi University Global COE Hi-Stat Discussion Paper Series No. 271, Hitotsubashi University.

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank Ralph Paprzycki for translation from the Japanese original and for comments.